MRI to visualize disruptions in several areas of the brain associated with attention and visual processing in Parkinson’s sufferers

Parkinson’s disease affects the central nervous system, mainly the motor system. The long term degenerative disease causes tremors, memory loss, difficulty walking, and shaking. Some with Parkinson’s even suffer from mild to severe hallucinations, up to 75%. These hallucinations can have a significant impact on the patients well being and cause them to become depressed or anxious, in addition to their other symptoms.

Recently, however, researchers from VU University Medical Center in Amsterdam used functional MRI (fMRI) to visualize disruptions in several areas of the brain associated with attention and visual processing in Parkinson’s sufferers. The findings could explain the visual hallucinations patients have.

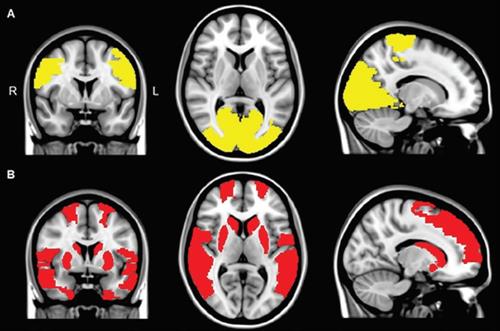

While Parkinson’s disease affects resting state functional connectivity of the posterior and paracentral brain regions, visual hallucinations are associated with a more global loss of network connectivity.

“Our findings argue against the notion that a single specific functional brain region or network is the neural substrate of visual hallucinations in Parkinson’s,” said lead author Dr. Dagmar Hepp from VUMC’s department of neurology and department of anatomy and neurosciences. “Rather, we supply further evidence for a more global loss of network efficiency, which could drive disturbed attentional and visual processing and thereby lead to visual hallucinations in Parkinson’s.”

Hepp added that “visual hallucinations are associated with cognitive problems and the development of dementia in Parkinson’s. Thus, the high prevalence and great impact of visual hallucinations in Parkinson’s prompted us to investigate the underlying processes with functional MRI to gain a better understanding of the symptom and, ultimately, provide clues for therapy.”

There have been previous studies done by Hepp and colleagues, exploring the cognitive problems in Parkinson’s patients with visual hallucinations, comparing them with patients who did not have visual hallucinations. During those studies using the MRI system, it was found that Parkinson’s patients with visual hallucinations had more severe attention and memory problems.

Parkinson’s patients with visual hallucinations were also discovered to have uncovered atrophy or shrinkage in specific brain areas by previous structural MRI system studies. Other papers have reported a reduction in brain volume or an increase in regional brain volume among those with Parkinson’s hallucinations.

“We speculated that functional MRI, which measures the communication between brain areas, may be a more sensitive marker and may identify brain areas or networks that show dysfunction in Parkinson’s patients with visual hallucinations and thereby aid in the unraveling of this frequent and troublesome symptom,” Hepp said.

This retrospective study included 15 Parkinson’s patients with visual hallucinations, 40 Parkinson’s patients with no visual hallucinations, and 15 control subjects. Every participant underwent structural whole-brain 3-tesla MRI system scans with a sagittal 3D T1-weighted fast-spoiled gradient-echo sequence. The researchers were then able to calculate mean functional connectivity between 47 regions of interest and compare the results with whole brain and region specific activity.

The Parkinson’s patients were asked about the presence of visual hallucinations through the Scales for Outcomes in Parkinson Disease Psychiatric Complications (SCOPA-PC) questionnaire. A score of at least 1 on the first item classified patients as having hallucinations, while a score of 0 classified them as not having hallucinations.

Cognitive capabilities were also evaluated with the Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) and the Cambridge Cognitive Examination (CC). The seven cognitive domains that the tests assess and score are: orientation, language, memory, attention and calculation, praxis, abstract thinking, and perception. A CCE score of less than 80 indicates dementia, while an MMSE score of at least 24 indicates normal cognition.

After the researchers reviewed the fMRI results, the researchers discovered significant differences in whole-brain mean functional connectivity between Parkinson’s patients and the control subjects. Further analysis showed that only the Parkinson’s patients with visual hallucinations had significantly lower whole-brain mean functional connectivity than control subjects; there was no statistically significant difference between the Parkinson’s patients with no visual hallucinations and control participants.

Get Started

Request Pricing Today!

We’re here to help! Simply fill out the form to tell us a bit about your project. We’ll contact you to set up a conversation so we can discuss how we can best meet your needs. Thank you for considering us!

Great support & services

Save time and energy

Peace of mind

Risk reduction

The Parkinson’s patients with visual hallucinations had reduced functional connectivity compared with the control subjects in nine brain regions. The underperforming regions were in the frontal cortex, temporal cortex, rolandic operculum, occipital cortex, and striatum and were related to cognitive deficits.

Eight regions in the occipital lobe and paracentral area where functional connectivity was less for both Parkinson’s patients with and without visual hallucinations, compared with the control participants, according to the regional connectivity analysis. These regions are associated with motor performance.

The cognitive tests also showed the differences between Parkinson’s patients and the controls in further detail. Global cognitive functioning scores in the CCE test were significantly lower among all Parkinson’s patients than for the control participants, but the results were comparable between the groups for the MMSE test.

As expected, Parkinson’s patients with visual hallucinations performed worse on a statistically significant basis than Parkinson’s patients with no visual hallucinations in orientation, language, memory, and perception on the CCE test.

Hepp said that there are no direct therapeutic implications for patient care based on research, even though the study provides new insights into the functional substrates of visual hallucinations in Parkinson’s patients.

‘Future studies could indicate whether techniques that could stimulate the areas with decreased connectivity in Parkinson’s patients with visual hallucinations – the areas that communicated less with the rest of the brain – could be helpful to treat visual hallucinations in Parkinson’s,” she said. “In addition, our findings may offer future markers to predict the occurrence of visual hallucinations in Parkinson’s patients.”

This research path with a longitudinal study is being planned by Hepp and colleagues, in order to see whether changes in functional connectivity could indeed predict the occurrence of visual hallucinations among Parkinson’s patients.

“Since the presence of visual hallucinations in Parkinson’s is often associated with more severe other motor symptoms, such as anxiety, depression, cognitive problems, and sleep disturbances, the presence of these symptoms should be included in such a longitudinal functional MRI analysis as well,” she said.